Why We Chose Buckfast Bees

When discussing beekeeping on the Isle of Lewis people spoke about a “Native Black Bee” or used the term “Hebridean Black Bee”. However there are few active beekeepers on the island and even fewer resources for information about the native Hebridean Black Bee. Having researched the case further I came to the conclusion that a truly native Hebridean bee is more of a wistful term, rather than a genetically unique species.

While the now-celebrated UK native black bee Apis mellifera mellifera (AMM) once thrived across Britain, including parts of Scotland, its numbers collapsed in the early 20th century due to the devastating Isle of Wight Disease and extensive hybridisation with imported strains.

There is little historical or other evidence that a genetically distinct, regionally adapted subspecies ever evolved specifically in the Outer Hebrides. Instead, what likely existed were scattered, isolated populations of AMM, the same dark bee found across much of northern and western Europe, that persisted in the Hebrides after the collapse of bee populations elsewhere. The islands’ remoteness may have shielded these bees somewhat from the hybridisation seen on the mainland, but they were not necessarily unique.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, efforts to conserve AMM brought renewed attention to these remote black bees. People began referring to dark bees in the Western Isles as Hebridean Black Bees, assuming continuity with pre-collapse populations. However, genetic studies show that even relatively pure populations are not genetically distinct from the broader northern group of European AMM.

The closest bees to the “Hebridean Black Bees” may be those that are currently conserved on Colonsay. These were intentionally introduced and selectively bred to maintain dark bee genetics. Beekeeper Andrew Abrahams began this work in the 1970s, and by 2013, the Scottish Government formalised protection of these bees through the Beekeeping (Colonsay and Oronsay) Order, banning the import of other subspecies. A noble mission and a place I hope to visit one day!

However, no such order exists for the Isle of Lewis, or the neighbouring islands.

Buckfast Bees for the Hebridees

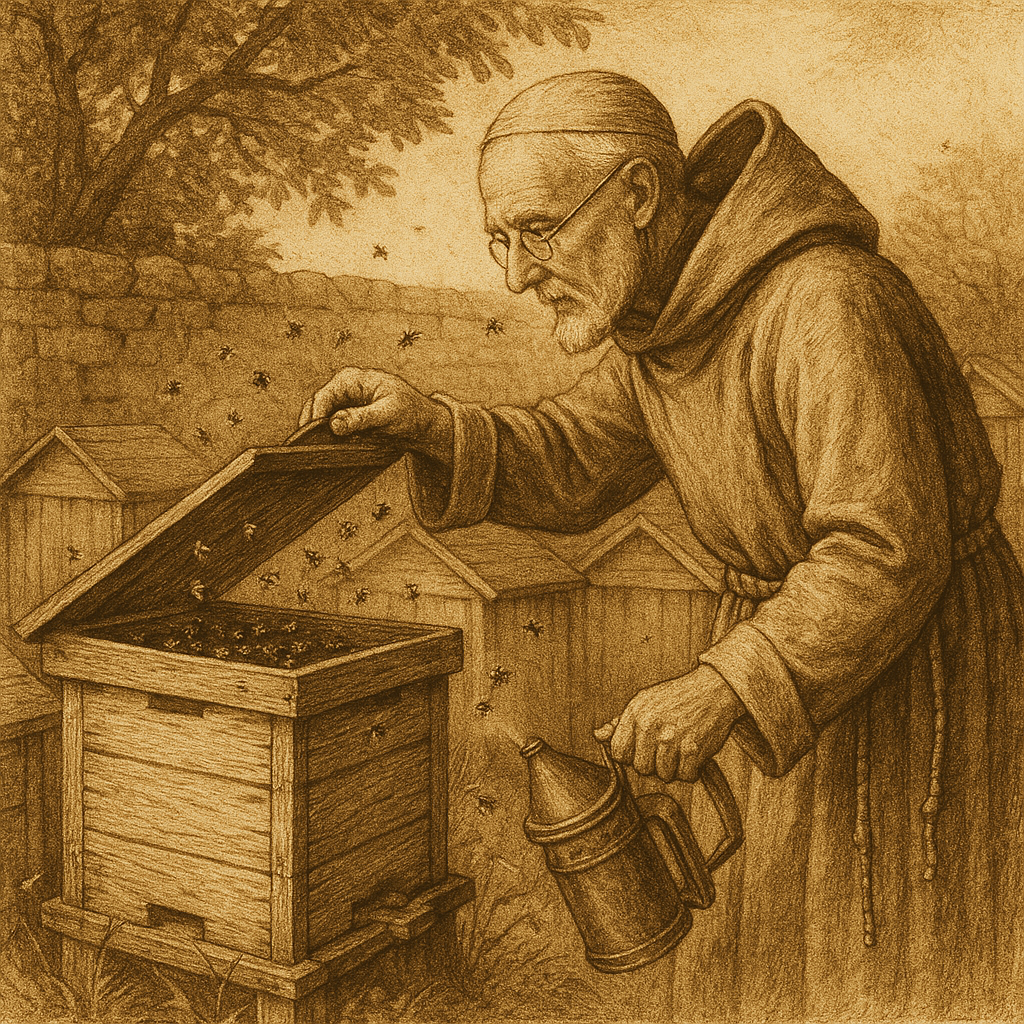

In contrast to the symbolic appeal of the elusive “Hebridean Black Bee”, the Buckfast bee, developed by Brother Adam at Buckfast Abbey, was a product of necessity. In the early 20th century, the native AMM population in the UK was devastated by Acarapis disease, or what became known as Isle of Wight Disease. This epidemic began around 1904 and swept through hives across the British Isles. It is understood to be caused by the parasite Nosema apis, often in combination with tracheal mites (Acarapis woodi), which affected the bees’ respiratory system and decimated UK and European black bee colonies.

At Buckfast Abbey in Devon, nearly all the abbey’s bees were wiped out. This loss prompted a young Brother Adam to begin a lifelong search for a more resilient strain. By selectively breeding survivors and importing hardy stock from across Europe and the Middle East, Brother Adam developed what we now call the Buckfast Bee. A hybrid designed for disease resistance, gentle temperament, and high productivity, all while being well-suited to northern climates.

These traits make the Buckfast bee especially well suited to beekeeiping in the UK and hopefully in the Outer Hebrides. There are few beekeepers on the island, and residents discuss the difficulties of keeping bees due to unpredictable weather, wet and windy conditions, and limited forage.

However these same challenges were met by keepers of old. Evidence of bee boles (holes built into walls to shelter skeps or hives from the weather) date back as far as the 12th century, and from the 19th century in rural Scotland where beekeeping became part of life despite the changeable weather.

While some advocate for using “native” bees, the reality is that Apis mellifera mellifera’s historical presence in the Hebrides was somewhat fragmented throughout history. The bees available from Colonsay, while valuable for conservation, did not convince me enough to dictate my choice of AMM over other, locally developed Buckfast lines.

Choosing Buckfast was a decision based on their performance, calmness, ease of management, thriftiness, and their excellent honey yields. After all, it is this yield of honey which we are seeking to produce here on the croft!

We have opted for a line of bee that has been adapted for varroa sensitive hygiene so as to prevent the spread of varroa and allow us to maintain the colony with no, or little, use of mite treatments.

Let the Journey Begin!

The Hebridean Black Bee is a compelling idea, and the native black bee was, perhaps, a real opportunity for us here in the Outer Hebrides. However I believe that the Buckfast bee offers a better fit for the needs of Croft 5. Sourced as locally as possible (at the same latitude and only 45 miles as the bee flies) and from a similar locale, the Buckfasts of the Hebrides should be well adapted for our environment of wind, rain and salty air!

I am looking forward to the challenge of beekeeping and honey production here on the Isle of Lewis. My primary goal is to produce honey so that Croft 5 can meet the demands of the island for local food and food security. For that we require practical, resilient, productive, and well-adapted bees. Exactly what I believe Brother Adam intended when he started his journey at Buckfast Abbey!

This is where his legacy continues and our story begins!

References

- Brother Adam. (1983). In Search of the Best Strains of Bees. Northern Bee Books.

- Ruttner, F. (1988). Biogeography and Taxonomy of Honeybees. Springer-Verlag.

- Moritz, R.F.A., Härtel, S., & Neumann, P. (2005). Global invasions of the western honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the consequences for biodiversity. Ecoscience, 12(3), 289–301.

- Jensen, A. B. et al. (2005). Quantifying honeybee mating range and isolation in semi-isolated valleys by DNA microsatellite paternity analysis. Conservation Genetics, 6(4), 527–537.

- Parejo, M. et al. (2016). Digging into the genomic past of Swiss honey bees by whole-genome sequencing museum specimens. Frontiers in Genetics, 7, 113.

- Scottish Government. (2013). The Beekeeping (Colonsay and Oronsay) Order 2013.

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2013/279/contents/made

Leave a Reply